The following discussions cover details of PyInstaller internal methods. You should not need this level of detail for normal use, but such details are helpful if you want to investigate the PyInstaller code and possibly contribute to it, as described in 如何贡献 .

There are many steps that must take place before the bundled script can begin execution. A summary of these steps was given in the Overview ( 一文件夹式程序如何工作 and 一文件式程序如何工作 ). Here is more detail to help you understand what the bootloader does and how to figure out problems.

The bootloader prepares everything for running Python code. It begins the setup and then returns itself in another process. This approach of using two processes allows a lot of flexibility and is used in all bundles except one-folder mode in Windows. So do not be surprised if you will see your bundled app as two processes in your system task manager.

What happens during execution of bootloader:

第一步:启动引导程序。

temppath

/_MEI

xxxxxx

.

temppath

/_MEI

xxxxxx

.

第二步:引导程序本身作为子级进程启动。

运行 Python 代码需要几个步骤:

frozen

and

_MEIPASS

到

sys

built-in module.

./eggs

目录。

Installing means appending .egg file names to

sys.path

.

Python automatically detects whether an

item in

sys.path

is a zip file or a directory.

PyInstaller

embeds compiled python code (

.pyc

files) within the executable.

PyInstaller

injects its code into the normal Python import mechanism. Python allows this; the support is described in

PEP 302

“New Import Hooks”.

PyInstaller implements the PEP 302 specification for importing built-in modules, importing “frozen” modules (compiled python code bundled with the app) and for C-extensions. The code can be read in

./PyInstaller/loader/pyi_mod03_importers.py

.

At runtime the PyInstaller

PEP 302

hooks are appended to the variable

sys.meta_path

. When trying to import modules the interpreter will first try PEP 302 hooks in

sys.meta_path

before searching in

sys.path

. As a result, the Python interpreter loads imported python modules from the archive embedded in the bundled executable.

This is the resolution order of import statements in a bundled app:

sys.builtin_module_names

.

package.subpackage.module

.pyd

or

package.subpackage.module

.so

.

sys.path

.

There could be any additional location with python modules

or

.egg

filenames.

ImportError

.

PyInstaller

manages lists of files using the

TOC

(Table Of Contents) class. It provides the

Tree

class as a convenient way to build a

TOC

from a folder path.

对象的

TOC

class are used as input to the classes created in a spec file. For example, the

脚本

member of an Analysis object is a TOC containing a list of scripts. The

pure

member is a TOC with a list of modules, and so on.

Basically a

TOC

object contains a list of tuples of the form

(

name

,

path

,

typecode

)

In fact, it acts as an ordered set of tuples; that is, it contains no duplicates (where uniqueness is based on the name element of each tuple). Within this constraint, a TOC preserves the order of tuples added to it.

A TOC behaves like a list and supports the same methods such as appending, indexing, etc. A TOC also behaves like a set, and supports taking differences and intersections. In all of these operations a list of tuples can be used as one argument. For example, the following expressions are equivalent ways to add a file to the

a.datas

成员:

a.datas.append( [ ('README', 'src/README.txt', 'DATA' ) ] ) a.datas += [ ('README', 'src/README.txt', 'DATA' ) ]

Set-difference makes excluding modules quite easy. For example:

a.binaries - [('badmodule', None, None)]

is an expression that produces a new

TOC

that is a copy of

a.binaries

from which any tuple named

badmodule

has been removed. The right-hand argument to the subtraction operator is a list that contains one tuple in which

name

is

badmodule

和

path

and

typecode

elements are

None

. Because set membership is based on the

name

element of a tuple only, it is not necessary to give accurate

path

and

typecode

elements when subtracting.

In order to add files to a TOC, you need to know the typecode values and their related path values. A typecode is a one-word string. PyInstaller uses a number of typecode values internally, but for the normal case you need to know only these:

| typecode | description | 名称 | path |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘DATA’ | Arbitrary files. | Run-time name. | Full path name in build. |

| ‘BINARY’ | A shared library. | Run-time name. | Full path name in build. |

| ‘EXTENSION’ | A binary extension to Python. | Run-time name. | Full path name in build. |

| ‘OPTION’ | A Python run-time option. | Option code | ignored. |

The run-time name of a file will be used in the final bundle. It may include path elements, for example

extras/mydata.txt

.

A

BINARY

file or an

EXTENSION

file is assumed to be loadable, executable code, for example a dynamic library. The types are treated the same.

EXTENSION

is generally used for a Python extension module, for example a module compiled by

Cython

.

PyInstaller

will examine either type of file for dependencies, and if any are found, they are also included.

The Tree class is a way of creating a TOC that describes some or all of the files within a directory:

Tree(

root

,

prefix=

run-time-folder

,

excludes=

string_list

,

typecode=

code

|

'DATA'

)

None

,

the tree files will be at

the top level of the run-time folder.

*.ext

, which causes files with this extension to be excluded

DATA

, which is appropriate for most cases.

例如:

extras_toc = Tree('../src/extras', prefix='extras', excludes=['tmp','*.pyc'])

This creates

extras_toc

as a TOC object that lists all files from the relative path

../src/extras

, omitting those that have the basename (or are in a folder named)

tmp

or that have the type

.pyc

. Each tuple in this TOC has:

extras/

filename

.

../src/extras

folder (relative to the location of the spec file).

DATA

(by default).

An example of creating a TOC listing some binary modules:

cython_mods = Tree( '..src/cy_mods', excludes=['*.pyx','*.py','*.pyc'], typecode='EXTENSION' )

This creates a TOC with a tuple for every file in the

cy_mods

folder, excluding any with the

.pyx

,

.py

or

.pyc

suffixes (so presumably collecting the

.pyd

or

.so

modules created by Cython). Each tuple in this TOC has:

../src/cy_mods

relative to the spec file.

EXTENSION

(

BINARY

could be used as well).

An archive is a file that contains other files, for example a

.tar

file, a

.jar

file, or a

.zip

file. Two kinds of archives are used in

PyInstaller

. One is a ZlibArchive, which allows Python modules to be stored efficiently and, with some import hooks, imported directly. The other, a CArchive, is similar to a

.zip

file, a general way of packing up (and optionally compressing) arbitrary blobs of data. It gets its name from the fact that it can be manipulated easily from C as well as from Python. Both of these derive from a common base class, making it fairly easy to create new kinds of archives.

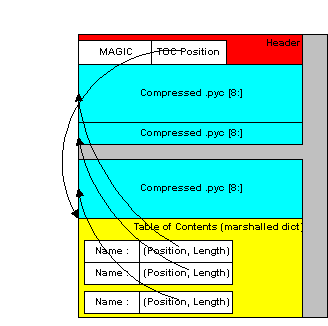

A ZlibArchive contains compressed

.pyc

or

.pyo

files. The

PYZ

class invocation in a spec file creates a ZlibArchive.

The table of contents in a ZlibArchive is a Python dictionary that associates a key, which is a member’s name as given in an

import

statement, with a seek position and a length in the ZlibArchive. All parts of a ZlibArchive are stored in the

marshalled

format and so are platform-independent.

A ZlibArchive is used at run-time to import bundled python modules. Even with maximum compression this works faster than the normal import. Instead of searching

sys.path

, there’s a lookup in the dictionary. There are no directory operations and no file to open (the file is already open). There’s just a seek, a read and a decompress.

A Python error trace will point to the source file from which the archive entry was created (the

__file__

attribute from the time the

.pyc

was compiled, captured and saved in the archive). This will not tell your user anything useful, but if they send you a Python error trace, you can make sense of it.

Structure of the ZlibArchive

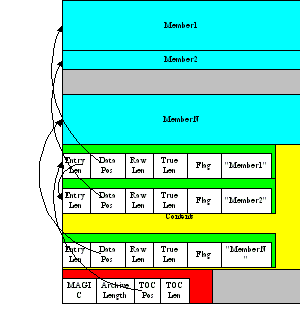

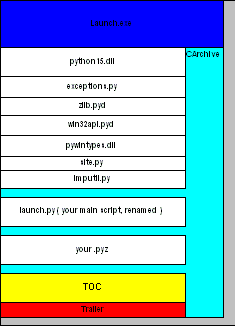

A CArchive can contain any kind of file. It’s very much like a

.zip

file. They are easy to create in Python and easy to unpack from C code. A CArchive can be appended to another file, such as an ELF and COFF executable. To allow this, the archive is made with its table of contents at the end of the file, followed only by a cookie that tells where the table of contents starts and where the archive itself starts.

A CArchive can be embedded within another CArchive. An inner archive can be opened and used in place, without having to extract it.

Each table of contents entry has variable length. The first field in the entry gives the length of the entry. The last field is the name of the corresponding packed file. The name is null terminated. Compression is optional for each member.

There is also a type code associated with each member. The type codes are used by the self-extracting executables. If you’re using a

CArchive

作为

.zip

file, you don’t need to worry about the code.

The ELF executable format (Windows, GNU/Linux and some others) allows arbitrary data to be concatenated to the end of the executable without disturbing its functionality. For this reason, a CArchive’s Table of Contents is at the end of the archive. The executable can open itself as a binary file, seek to the end and ‘open’ the CArchive.

Structure of the CArchive

Structure of the Self Extracting Executable

使用

pyi-archive_viewer

command to inspect any type of archive:

pyi-archive_viewer

archivefile

With this command you can examine the contents of any archive built with

PyInstaller

(

PYZ

or

PKG

), or any executable (

.exe

file or an ELF or COFF binary). The archive can be navigated using these commands:

PYZ-00.pyz

archive inside it.

Go up one level (back to viewing the containing archive).

Quit.

pyi-archive_viewer

command has these options:

| -h , --help | Show help. |

| -l , --log | Quick contents log. |

| -b , --brief | Print a python evaluable list of contents filenames. |

| -r , --recursive | |

| Used with -l or -b, applies recursive behaviour. | |

You can inspect any executable file with

pyi-bindepend

:

pyi-bindepend

executable_or_dynamic_library

pyi-bindepend

command analyzes the executable or DLL you name and writes to stdout all its binary dependencies. This is handy to find out which DLLs are required by an executable or by another DLL.

pyi-bindepend

用于

PyInstaller

to follow the chain of dependencies of binary extensions during Analysis.

In certain cases it is important that when you build the same application twice, using exactly the same set of dependencies, the two bundles should be exactly, bit-for-bit identical.

That is not the case normally. Python uses a random hash to make dicts and other hashed types, and this affects compiled byte-code as well as PyInstaller internal data structures. As a result, two builds may not produce bit-for-bit identical results even when all the components of the application bundle are the same and the two applications execute in identical ways.

You can assure that a build will produce the same bits by setting the

PYTHONHASHSEED

environment variable to a known integer value before running

PyInstaller

. This forces Python to use the same random hash sequence until

PYTHONHASHSEED

is unset or set to

'random'

. For example, execute

PyInstaller

in a script such as the following (for GNU/Linux and OS X):

# set seed to a known repeatable integer value PYTHONHASHSEED=1 export PYTHONHASHSEED # create one-file build as myscript pyinstaller myscript.spec # make checksum cksum dist/myscript/myscript | awk '{print $1}' > dist/myscript/checksum.txt # let Python be unpredictable again unset PYTHONHASHSEED